Working on an Agile team can really suck. But, why? No structure at all sucks way more. We should talk about that, too.

The first startup that I joined, in 2000 and at the height of the dot-com boom, was called WHnetworks.

I was just a kid of twenty years old and didn’t really understand what immense disorder I was being exposed to. WHnetworks were building a website where any user could ask any question, and the community would strive to answer it. It wasn’t focused on any specific niche. They had a thriving set of users who were rewarded by a points system that awarded points for good answers. It was the early 2000s, and this was innovative.

At the time, I was early in my design career, and I’d been hired to do special caricatures of users. When you hit a certain points threshold, you became an elite member of the site who had an illustrated avatar. This system made the power users of the site really stand out, and it successfully drove engagement and usage of the website. It also gave me a job, which I liked.

What I remember from that experience was a general sense of chaos. There were no paying customers, there was no apparent business vision, and the product was all over the place.

Crunchbase and its data don’t seem to go back that far so it is impossible to say what kind of funding WHnetworks got. My memories are fuzzy, but I remember fancy offices and catered food. I’d guess that I was there less than a year before the company’s runway was burned on those fancy offices, that catered food, and the high salaries that I assumed everyone was getting. I certainly wasn't worth what they were paying me. That’s the way things were back then. You went fast, and if you were lucky, you flew. If you were unlucky, you crashed and burned. WHnetworks wasn’t lucky, and it crashed and burned.

As I slowly, grumpily drifted my way up to management positions over the course of my career, I developed a set of strong opinions on what I think are the right ways to lead development and product teams. Twenty plus years on, I look back on WHnetworks and remember a team that was dysfunctional and lacked clear methodologies that would have enabled its members to quickly iterate, manage stakeholder expectations, and find their place in the market. They just did work because at that moment they thought it was the right thing.

These ideas that I have about how to manage teams developed largely in reaction to frustrating experiences like WHnetworks. On occasion, I was lucky enough to also experience really great, thoughtful leadership that I try to emulate in my own way.

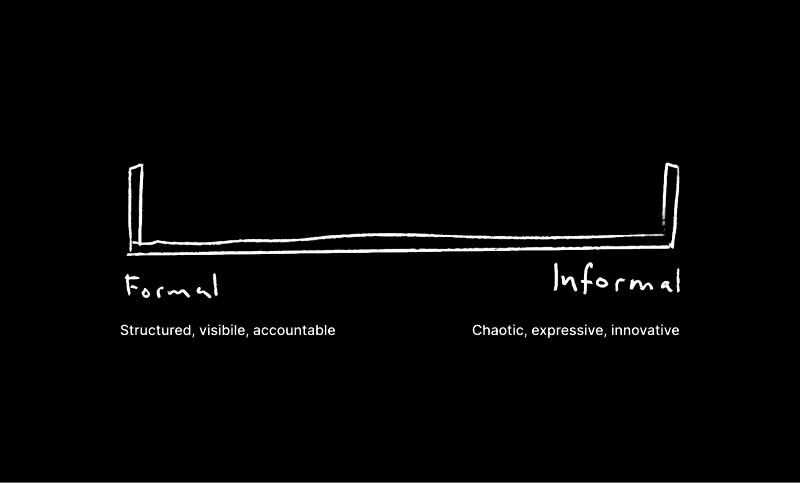

The Work Structure Spectrum

How people work in teams is a spectrum from highly formal to highly informal. On one end, you have approaches that aim to provide absolute visibility for stakeholders and total accountability from developers. On the other end you have none of that, and trade these features for complete developer freedom and stakeholders that are in the dark.

On its face, this seems like an obvious choice as to where on the spectrum you’d want to be. Who doesn’t want visibility and accountability? The more subtle truth is that visibility and accountability have costs that can slow down the pace of development or grind innovation to a halt. The same can be said of developer freedom, which, when it is total, can turn a viable business into a crater.

On the one hand, no stakeholder wants to hire a team of workers and have no idea what they are doing, and no exec wants late-in-the-game surprises that derail business efforts. On the other hand, no developer wants to have someone looking over their shoulder at every detail of what they do. No developer wants to be stuck in endless, formal process meetings when they could be solving technical problems instead.

Stakeholders want to know their needs are being met. Developers want the freedom to explore, to experiment, and to be creative.

The processes that you put in place need to meet both sets of needs. If you want to achieve something meaningful, you can't have choking order, and you can't have chaos.

The worst experiences that I’ve had seem to share a few key similarities in what made their processes so bad.

Lack of product clarity – If you don’t know exactly what you’re working on, you’ll build more iterations and worse-quality software.

Process for its own sake – What works at company A will not necessarily work at company B. They aren’t composed of the same people, the same experiences, or the same challenges.

Stuck on legacy – It can be hard to make meaningful organisational changes because your team has already grown accustomed to working a certain way.

Lack of trust – Stakeholders don’t trust developers, developers don’t trust stakeholders.

As we said before, you’re trying to strike a smart balance between too much order and too much chaos. You can’t just drop “Agile” or “Scrum” on a team and expect them to build the right thing, fast. That’s how you end up with angry stakeholders and miserable developers.

You should instead slowly and carefully add processes that fit your actual needs as a group. The affected teams should be provided explanations as to why these processes are being added, and they should be able to give input so that they can understand the need.

There should also always be the option to reduce the amount of formal process if you can.

Meetings can be soul draining - It’s ok to remove meetings that your team doesn't find truly valuable.

Limit meeting participants - Not everybody needs to be in every meeting. If you find that you have ten people in a meeting and only two are talking, maybe you’re wasting a lot of people’s valuable time.

Don’t just go through the motions - A lot of formal processes have strict requirements for standups, reviews, retrospectives, and post-mortems. You may not really need all of them. If you find that your team just goes through the motions (miserably), then maybe you need to drop some and find alternatives for those specific functions.

Find alternative ways to share information in a team - If you find that your team is having problems communicating, maybe you need an alternative methodology. Better documentation, for example, can be an excellent alternative for highly remote, distributed teams to transfer knowledge and state internally.

What you truly build when you build a team, and processes to support them, is a way to effectively communicate. You are providing clarity, support, and a way to manage change. It’s a way for those with vested interests to talk to those who are building, and a way for those who are building to talk back.

Article Addendum

I hope you enjoyed this article!

Without direct feedback it can be hard to iterate, and I value your thoughts immensely. Please send me an email if you find a typo or disagree with the content. I'm always up for a vigorous and lively debate!